A Brief History of Lambic in Belgium: Difference between revisions

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

The tradition of brewing wheat-based beers extended forward from the days of the Gauls and permeated most of what is modern day Belgium and Germany. Sadly, much of the history of brewing lambic was never recorded and what is left are largely educated guesses based on the number of breweries licensed to operate in and around the Brussels area that likely produced some form of lambic, an extensive list of [[List_of_Closed_Lambic_Breweries_and_Blenders|brewers, blenders, and cafés]] that are no longer in operation, and anecdotal accounts like those of Jef Lambic in ''[[Books#Les_Memoirs_de_Jef_Lambic| Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic]]''. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, brewers were generally considered artisans and were mainly part of the agrarian community.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> This meant that many of the brewers were themselves farmers or had close family or community ties to the farmers in the community who supplied the raw materials for making beer. | The tradition of brewing wheat-based beers extended forward from the days of the Gauls and permeated most of what is modern day Belgium and Germany. Sadly, much of the history of brewing lambic was never recorded and what is left are largely educated guesses based on the number of breweries licensed to operate in and around the Brussels area that likely produced some form of lambic, an extensive list of [[List_of_Closed_Lambic_Breweries_and_Blenders|brewers, blenders, and cafés]] that are no longer in operation, and anecdotal accounts like those of Jef Lambic in ''[[Books#Les_Memoirs_de_Jef_Lambic| Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic]]''. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, brewers were generally considered artisans and were mainly part of the agrarian community.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> This meant that many of the brewers were themselves farmers or had close family or community ties to the farmers in the community who supplied the raw materials for making beer. | ||

In 1839, the area in which lambic could legally be brewed was limited to “Brussels and the immediately surrounding area”, and, according to Van den Steen (2012), “until 1860, ‘foreign’ beers whether imported or [domestically] produced were virtually non-existent in Brussels.”<ref name=GeuzeKriek>Jef Van den Steen, [[Books#Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer|Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer]], 2012</ref> By 1860 this region was extended to a two-mile zone around the capital city of Brussels. The reason for this zone of protection was likely due to the fact that many brewers making a living in the area believed that the unique process used to create lambic also included unique micro flora that could only be found in the immediate area surrounding Brussels. However, in 1904 a Danish scientist by the name of Niels Kjelte Claussen was able to demonstrate that some of the same yeast present in lambics was also present in British beers. Claussen chose to classify the yeast as brittanomyces, but a typesetting issue caused the publication to be printed as brettanomyces. The yeast is still known by this name today, though in 1921 scientists also discovered more distinct strains of brettanomyces in lambic beers naming them bruxellenis and lambicus.<ref name=GeuzeKriek>Jef Van den Steen, [[Books#Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer|Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer]], 2012</ref><ref name=LambicLand>Tim Webb, Chris Pollard, Siobhan McGinn, [[Books#LambicLand: A Journey Round the Most Unusual Beers in the World|LambicLand: A Journey Round the Most Unusual Beers in the World]] </ref> | In 1839, the area in which lambic could legally be brewed was limited to “Brussels and the immediately surrounding area”, and, according to Van den Steen (2012), “until 1860, ‘foreign’ beers whether imported or [domestically] produced were virtually non-existent in Brussels.”<ref name=GeuzeKriek>Jef Van den Steen, [[Books#Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer|Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer]], 2012</ref> By 1860 this region was extended to a two-mile zone around the capital city of Brussels. The reason for this zone of protection was likely due to the fact that many brewers making a living in the area believed that the unique process used to create lambic also included unique micro flora that could only be found in the immediate area surrounding Brussels. However, in 1904 a Danish scientist by the name of Niels Kjelte Claussen was able to demonstrate that some of the same yeast present in lambics was also present in British beers. Claussen chose to classify the yeast as brittanomyces, but a typesetting issue caused the publication to be printed as brettanomyces. The yeast is still known by this name today, though in 1921 scientists also discovered more distinct strains of brettanomyces in lambic beers naming them bruxellenis and lambicus.<ref name=GeuzeKriek>Jef Van den Steen, [[Books#Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer|Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer]], 2012</ref><ref name=LambicLand>Tim Webb, Chris Pollard, Siobhan McGinn, [[Books#LambicLand: A Journey Round the Most Unusual Beers in the World|LambicLand: A Journey Round the Most Unusual Beers in the World]], 2010 </ref> | ||

Around the same time as the brewing processes were being worked out, the aforementioned Jef Lambic was writing his manuscript providing an overview of the Brussels lambic culture from a social perspective. The author, who was the son of a lambic brewer at [[Brasserie_De_Keersmaeker|Brouwerij De Keersmaeker]] (later known as [[Brasserie_Mort_Subite|Mort Subite]]), describes the lambic cafés of the day as chic meeting places for both the upper and working classes. He also discusses the invasion of the “brown beers” in the 19th century.<ref name=JefLambic>Jef Lambic, [[Books#Les_Memoirs_de_Jef_Lambic| Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic]], ~1955 </ref> These bottom fermented German beers was cause for concern to many brewers in Brussels and Belgium alike when they first began appearing in the 1860’s.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> | Around the same time as the brewing processes were being worked out, the aforementioned Jef Lambic was writing his manuscript providing an overview of the Brussels lambic culture from a social perspective. The author, who was the son of a lambic brewer at [[Brasserie_De_Keersmaeker|Brouwerij De Keersmaeker]] (later known as [[Brasserie_Mort_Subite|Mort Subite]]), describes the lambic cafés of the day as chic meeting places for both the upper and working classes. He also discusses the invasion of the “brown beers” in the 19th century.<ref name=JefLambic>Jef Lambic, [[Books#Les_Memoirs_de_Jef_Lambic| Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic]], ~1955 </ref> These bottom fermented German beers was cause for concern to many brewers in Brussels and Belgium alike when they first began appearing in the 1860’s.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:19, 2 February 2017

A Brief History of Lambic in Belgium

The story of lambic in the Belgian culture is a complex history that dates back to the times of the Roman Empire. From conquest and conquer in ancient times, to World Wars, taxation, decline in popularity, and resurgence, lambic has continued to persevere and evolve. Today, lambic is experiencing a renaissance in Belgium, across Europe, and across the world.

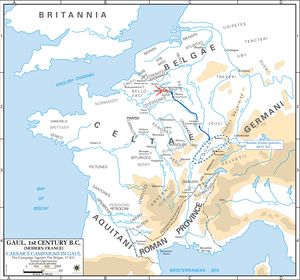

Beer, the Belgae, and the Romans

After completing campaigns against southern Gallic and Germanic tribes in 57 BC, Julius Caesar moved north and west to tend to a revolt from the Belgae Gauls living between the Senne and Rhine Rivers in what is now modern day Belgium and Germany. Caesar noted both the ferocity of the Belgians and their connection to the Germanic tribes he had just conquered. This close cultural and economic relationship also included a close connection to beer. Unlike the Mediterranean cultural centers, the Germanic and Gallic tribes viewed wine as an effeminate beverage and banned its import.[1]

The Roman historians marching with the army at the time also noted the abundance of cereals growing in northern Gaul and that the Belgae themselves were using these cereals to make beer. The evidence from throughout the region, inscriptions referring to breweries near the modern day Belgian/German border and remains of breweries in Germany and the Belgian city of Namur, also points to wheat as being the primary cereal used for brewing at the time. Indeed an inscription from a cup found near Mainz, Germany, which at the time would have been part of the contiguous northern Gaul territory, reads in part, “Waitress, fill up the pot from the good wheat beer!” Other inscriptions also note that there was a guild of beer makers spanning into the middle ages.[1][2]

These fermented beverages, only precursors to modern day controlled fermentation beers, were most certainly spontaneously fermented in the same way that lambic wort is spontaneously fermented today, though with the brewers having little accurate knowledge of the process.

The First Representations of Lambic

Buren (1992) recounts two stories, one of which he notes is from a long out of print manuscript, of Keizer Karel (better known as King Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) and his fondness for lambic, which at the time would have been blended with a younger mars beer to give it a sweeter taste. His reign from 1519-1556 was filled with many travels that included trips through Brussels and Belgium in general. On one such trip he is said to have passed through a pub and demanded to a waitress, “Serve me a lambic!” After several servings of a lambic from a pitcher (as much as three liters) a drunk Charles proceeds to accost the blonde waitress finally managing to kiss her backside.[3]

As early as the 1400s, but certainly by 1559, the specific ratios for brewing what would become known as lambic were already being laid out. A tax collector in the city of Halle had specified that beer brewed in the town should be brewed with a specific ratio of barley to wheat in order to control revenues based on crop harvests. Around the same time, beer, which was always a drink popular with the peasantry, was becoming more prominent in Renaissance art. Many believe that the first historical depiction of this stoneware being used for lambic (more specifically Faro) is in Pieter Bruegel's painting The Peasant Wedding (Le Repas de noce, French, De boerenbruiloft, Dutch).[3] Completed ca. 1567-68, the painting depicts a wedding ceremony in which stone pitchers are used for serving beer to guests.

Lambic in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries

The tradition of brewing wheat-based beers extended forward from the days of the Gauls and permeated most of what is modern day Belgium and Germany. Sadly, much of the history of brewing lambic was never recorded and what is left are largely educated guesses based on the number of breweries licensed to operate in and around the Brussels area that likely produced some form of lambic, an extensive list of brewers, blenders, and cafés that are no longer in operation, and anecdotal accounts like those of Jef Lambic in Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, brewers were generally considered artisans and were mainly part of the agrarian community.[4] This meant that many of the brewers were themselves farmers or had close family or community ties to the farmers in the community who supplied the raw materials for making beer.

In 1839, the area in which lambic could legally be brewed was limited to “Brussels and the immediately surrounding area”, and, according to Van den Steen (2012), “until 1860, ‘foreign’ beers whether imported or [domestically] produced were virtually non-existent in Brussels.”[5] By 1860 this region was extended to a two-mile zone around the capital city of Brussels. The reason for this zone of protection was likely due to the fact that many brewers making a living in the area believed that the unique process used to create lambic also included unique micro flora that could only be found in the immediate area surrounding Brussels. However, in 1904 a Danish scientist by the name of Niels Kjelte Claussen was able to demonstrate that some of the same yeast present in lambics was also present in British beers. Claussen chose to classify the yeast as brittanomyces, but a typesetting issue caused the publication to be printed as brettanomyces. The yeast is still known by this name today, though in 1921 scientists also discovered more distinct strains of brettanomyces in lambic beers naming them bruxellenis and lambicus.[5][6]

Around the same time as the brewing processes were being worked out, the aforementioned Jef Lambic was writing his manuscript providing an overview of the Brussels lambic culture from a social perspective. The author, who was the son of a lambic brewer at Brouwerij De Keersmaeker (later known as Mort Subite), describes the lambic cafés of the day as chic meeting places for both the upper and working classes. He also discusses the invasion of the “brown beers” in the 19th century.[7] These bottom fermented German beers was cause for concern to many brewers in Brussels and Belgium alike when they first began appearing in the 1860’s.[4]

Lambic ca.1900 – 1948

Through the late 1800s, bottled lambic was still relatively uncommon due to the difficulty of controlling the fermentation and having bottles explode. The 'gueuze-lambics' were showcased at the 1897 World’s Fair in Brussels and started to gain some popularity outside of the area after having been a relatively localized production. By 1900, Kriek lambic had already been popularized, and an early mention of framboise lambic occurred around 1909-10. Paul Cantillon, of Brasserie Cantillon stated that they had more bottles of Framboise than of Kriek in his inventory for 1909-1910, which was reaffirmed by Jean Van Roy during the Lambic Summit, 2010.[8][9] In 1919 a law banning spirit drinks from cafés in Belgium was passed, though not often enforced.[4] The First World War brought with it a great challenge for the brewing industry in Belgium in general. Occupying forces confiscated brewing equipment or forced breweries to brew German-style beers, food was rationed, and brewers were forced to shut down.[5]

This temporary slowdown in the Belgian brewing industry also opened the path for a resurgence of cheaply and quickly made beers. However, after the war it became apparent that lambic was again on the rise with many breweries including Cantillon to ramp up production. The first specialized and branded lambic glasses made an appearance and the café scene was still vibrant with many café blenders.[5] Sweetened gueuze, created by adding sugar directly to the glass also started to gain popularity. However, this growth would be short lived as the Second World War began to spread across Europe. This again caused breweries to shut down or retool due to occupation and supply shortages.

Postwar Lambic

The immediate postwar lambic scene in and around Brussels saw both boom and bust. Large breweries like Belle Vue had remained prosperous during wartime by purchasing other smaller breweries, while other breweries struggled to remain relevant while continuing to deal with a poor economy and rationed food and supplies. The solution to some of the problems came in the form of sweetened, commercialized lambic.

Though already in existence before World War II, the success of colas and soft drinks inspired a new drinking trend in Belgium and across Europe.[5] The sweetened lambic became extremely popular. During World War II, those brewers who were still able to brew were severely restricted in terms of the quality and quantity of their ingredients. In order to continue producing kriek, many brewers added extra flavorings and colorings to combat the lack of available fruits.

A similar situation arose with geuze as well. This capsulekengeuze, which was generally comprised of a blend of lambic and top-fermented beer, was filtered, pasteurized, sweetened, pressurized with CO2 and bottled into 25cl bottles. Many breweries at the time adopted this model as a means to survive. This created some confusion in labeling, and in 1965 a royal order began to regulate terms like geuze and how they would be used. The tradition of sweetening lambic continued to grow immensely through the latter half of the 20th century with breweries like Lindemans, De Troch, and Belle Vue producing massive quantities of sweetened lambic. Very few producers were still following the old ways of production.

Lambic ca.1970 – 1999

As mergers and acquisitions continued to close smaller breweries, some breweries managed to remain open and independent. Survival mechanisms like sweetened lambic and side businesses persisted throughout the 70's, and still continue to this day. Brewers still cater to what a majority of consumers want and often expect, and that is sweetened lambic. Still, brewers like Armand Debelder who do not offer sweetened lambic survived by maintaining a restaurant with his brother that was connected to 3 Fonteinen.[10]

In 1978, Jean Pierre Van Roy of Cantilon opened the brewery up as a ‘living museum’. The Brussels Gueuze Museum (Musée bruxellois de la gueuze) was born. The museum strived to preserve the process and qualities of centuries old production techniques in the modern era. Today, it is one of the most frequented stops on any lambic pilgrimate to Brussels. If the era immediately following World War II saw a surge in sweetened lambic, then the 1970’s onward has seen a distinct split in lambic production, appellation, and consumption.

Sweetened lambic is still extremely popular, yet so is the ‘traditional’ unsweetened lambic. From hundreds of producers in the early part of the 20th century, the current lambic lineup includes nine lambic brewers (who also blend) and four lambic blenders. Though small in number, these brewers and blenders represent a new resurgence in lambic interest. Many brewers who had long since abandoned the idea of non-sweetened lambics are back to producing both sweetened and unsweetened products for consumers. In 1994, Lindemans reintroduced an unsweetened gueuze called Gueuze Cuvée René, and Timmermans has also reintroduced a line of unsweetened products.

As lambic brewers and blenders began to recognize the importance of keeping the older traditions alive, some banded together to form HORAL. This group aims to promote lambic beers, brewing, and culture in Belgium. Their stated goals are "to promote the craft lambic beers and related products, paying attention to the entire process of brewing to serving lambic; denouncing irregularities concerning artisanal lambic beers and related products; take steps to protect the traditional lambic beers and related products."[11] HORAL has worked to obtain and maintain current European Protections on traditional lambic beers since the Traditionally Specialty Guaranteed label was assigned to them in 1997.[12]

Lambic 2000 - Present

This renewed interest in lambic has inspired new generations of brewers, blenders, and consumers alike. The most recent commercial blender, Gueuzerie Tilquin opened its doors in 2011 and has been well received by the lambic community both at home and abroad. Breweries continue to experiment with new lambics, classics are reemerging, and lambic events, museums, and breweries are seeing record numbers of attendees visitors. The new chapter in the history of lambic is currently being written, and the recent surge in popularity and the return of more traditional products is a welcome sign of things to come.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Max Nelson, The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe, 2005

- ↑ Patrick McGovern, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages, 2010

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Raymond Buren, Gueuze, Faro, et Kriek, 1992

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jean-Xavier Guinard, Classic Beer Styles: Lambic, 1990

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Jef Van den Steen, Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer, 2012

- ↑ Tim Webb, Chris Pollard, Siobhan McGinn, LambicLand: A Journey Round the Most Unusual Beers in the World, 2010

- ↑ Jef Lambic, Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic, ~1955

- ↑ http://www.cantillon.be/br/3_103 Cantillon Rosé De - Gambrinus

- ↑ The Lambic Summit, Part 16

- ↑ The Lambic Summit, Part 10

- ↑ HORAL - Association, Members, and History, http://www.horal.be/vereniging (Dutch)

- ↑ Tessa Avermaete and Gert Vandermosten, Traditional Belgian Beers in a Global Market Economy, 2009