The Language of Lambic: Difference between revisions

| (59 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==The Language of Lambic: Linguistic Differentiation in Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French Lambic Terminology== | [[An_Overview_of_Lambic|← An Overview of Lambic]] | ||

==The Language of Lambic: Linguistic Differentiation and Etymological History in Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French Lambic Terminology== | |||

Making sense of the terminology surrounding lambic can be as complex as the beer itself. Belgium is a country divided into very distinct linguistic regions whose inhabitants have their own words for many of the commonly used terms associated with the lambic tradition and process. Both Dutch and French speaking brewers and blenders are in operation today leaving many curious lambic drinkers wondering how this all came to be. In addition to the following article, readers may also find the [[Glossary|Lambic.Info Glossary]] a helpful resource as they browse this site. | |||

==Introduction== | |||

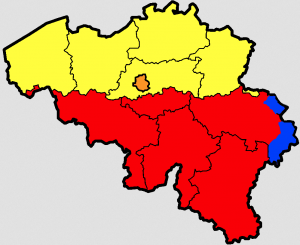

The language diversity contained within the modern-day borders of Belgium provides a source of constant linguistic conflict in the Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French speaking populations that dominates 94% of the population (56% and 38% respectively as a first language). | The language diversity contained within the modern-day borders of Belgium provides a source of constant linguistic conflict in the Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French speaking populations that dominates 94% of the population (56% and 38% respectively as a first language). Looking at a linguistic map of Belgium one notices that the capital of Brussels is squarely planted in an area dominated by the Belgo-Dutch dialect (sometimes referred to as Flemish in English). The capital area is officially regarded as bilingual by the Belgian government, but a survey of languages overheard walking around town leans toward the Bruxellois dialect of French. The dichotomy between these Belgo-Dutch speakers and Belgo-French speakers plays out on a number of social and political levels throughout the country, and within the lambic brewing and blending community one can still see and hear the differences today. The purpose of this article is to explore the historical, etymological, linguistic, and orthographic differences found among lambic terminology, labeling, and appellation. This article freely switches between Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French where appropriate, though the orthographic difference is often minimal. | ||

==Overview of Linguistic and Administrative Divisions in Belgium== | |||

[[File:Belgium provinces regions striped.png|thumb|Map indicating the language areas of provinces of Belgium. Thinner black lines mark provinces. Yellow is Dutch-speaking/Flemish Region, red is French-speaking/Walloon region, blue is German-speaking, and orange is bilingual Dutch-French/Brussels Capital region. | |||

Source: wikipedia]] | |||

To fully understand how the language of lambic came to be used among the brewers, it is first necessary to have a general overview of how the country of Belgium is administered. Belgium is divided into three regions, three communities, and four language areas. The three regions compose of the Flemish region (Dutch speaking), the Brussels-Capital region (officially bilingual), and the Walloon region (French speaking). Within the Flemish and Walloon regions there are five provinces each. The Belgian-Capital region does not have any official provincial designation nation and acts as its own community. The fourth language area is a small minority of German speaking Belgians in the east of the country. | |||

The provincial divisions in the Flemish Region are West Flanders, East Flanders, Antwerp, Flemish Brabant, and Limburg. The provincial divisions in the Walloon region are Hainaut, Walloon Brabant, Namure, Liège, and Luxembourg. It is important to note that most lambic breweries and blenders fall into either the Flemish region or the Brussels-Capital regions. From here, the brewery's languages can now be better understood. | |||

==Brewery Locations== | |||

Most present-day lambic breweries and blenders, as well as those that are no longer in operation, are situated in and around the [[An_Overview_of_Lambic#Lambic_Geography|Zenne valley]] in the [[An_Overview_of_Lambic#Lambic_Geography|Pajottenland]] area of Belgium. This area, consisting of mostly farmland, is part of the Flemish Brabant province and sits just west of the Brussels capital area. Though Brussels is primarily Belgo-French speaking, the area that surrounds the city to the north, east, and west is predominantly Belgo-Dutch speaking. This has led to very few breweries actually using the French terminology in lambic brewing on a consistent basis over the years. Currently, the only truly traditional lambic brewery located in Brussels using primarily French terminology for labeling, press, and first language tours is [[Brasserie Cantillon|Brasserie Cantillon]]. | |||

Most present-day lambic breweries and blenders as well as those that are no longer in operation are situated in and around the [[ | |||

The only traditional lambic blender outside of Brussels currently using French terminology is [[Gueuzerie Tilquin|Gueuzerie Tilquin]]. Located in the town of Bierghes, in the Senne valley, it is the only gueuze blender in the primarily French-speaking Walloon Brabant region situated within the administrative commune of Rebecq. Two less-than-traditional lambic breweries, [[Brasserie Mort Subite|Brasserie Mort Subite]] and [[Brasserie Belle Vue|Brasserie Belle-Vue]], currently use French terminology, however; only Brasserie Belle-Vue is located in Brussels. It is currently owned by the international conglomerate of Anheuser-Busch InBev whose European headquarters are located in the Dutch-speaking city of Leuven east of Brussels. The rest of the prominent lambic brewers and blenders are mostly situated west/southwest of Brussels and primarily use the Belgo-Dutch dialect. | The only traditional lambic blender outside of Brussels currently using French terminology is [[Gueuzerie Tilquin|Gueuzerie Tilquin]]. Located in the town of Bierghes, in the Senne valley, it is the only gueuze blender in the primarily French-speaking Walloon Brabant region situated within the administrative commune of Rebecq. Two less-than-traditional lambic breweries, [[Brasserie Mort Subite|Brasserie Mort Subite]] and [[Brasserie Belle Vue|Brasserie Belle-Vue]], currently use French terminology, however; only Brasserie Belle-Vue is located in Brussels. It is currently owned by the international conglomerate of Anheuser-Busch InBev whose European headquarters are located in the Dutch-speaking city of Leuven east of Brussels. The rest of the prominent lambic brewers and blenders are mostly situated west/southwest of Brussels and primarily use the Belgo-Dutch dialect. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 20: | ||

The names of cities that breweries use in their official addresses give a good idea of the general linguistic approach taken by the company. Many towns in Belgium, regardless of their regional location have both a French and a Dutch name. Some brewers have historically used both names in labeling, while others have stuck to one. The following table shows a list of currently operating brewers and blenders, their locations in both Dutch and French (if available), and their preferred use. | The names of cities that breweries use in their official addresses give a good idea of the general linguistic approach taken by the company. Many towns in Belgium, regardless of their regional location have both a French and a Dutch name. Some brewers have historically used both names in labeling, while others have stuck to one. The following table shows a list of currently operating brewers and blenders, their locations in both Dutch and French (if available), and their preferred use. | ||

<< | <center> | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; " | |||

! style="width:100px;"|Brewer | |||

! style="width:250px;"|Province | |||

! style="width:150px;"|Town/Village (Dutch) | |||

! style="width:150px;"|Town/Village (French) | |||

!Currently using: | |||

|- | |||

| 3 Fonteinen||Vlaams-Brabant||Beersel||N/A||Dutch | |||

|- | |||

| Belle-Vue||Vlaams-Brabant||Sint-Pieters-Leeuw||Leeuw-Saint-Pierre||French | |||

|- | |||

| Boon||Vlaams-Brabant||Lembeek||Lembecq||Dutch | |||

|- | |||

| Cantillon||Région de Bruxelles-Capitale||Brussel||Bruxelles||French | |||

|- | |||

| De Cam||Vlaams-Brabant||Gooik||N/A||Dutch | |||

|- | |||

| De Troch||Vlaams-Brabant||Wambeek||N/A||Dutch, some French | |||

|- | |||

| Girardin||Vlaams-Brabant||Sint-Ulriks-Kapelle||Chapelle-Saint-Ulric||Dutch, some French | |||

|- | |||

| Hanssens||Vlaams-Brabant||Dworp||Tourneppe||Dutch | |||

|- | |||

| Lindemans||Vlaams-Brabant||Vlezenbeek||N/A||Dutch, some French | |||

|- | |||

| Mort Subite||Vlaams-Brabant||Kobbegem||Kobbeghem||Dutch, some French | |||

|- | |||

| Oud Beersel||Vlaams-Brabant||Beersel||N/A||Dutch | |||

|- | |||

| Timmermans||Vlaams-Brabant||Itterbeek||N/A||Dutch, some French | |||

|- | |||

| Tilquin||Province du Brabant wallon||Roosbeek||Rebecq-Rognon||French | |||

|} | |||

</center> | |||

==The Town of Lembeek== | |||

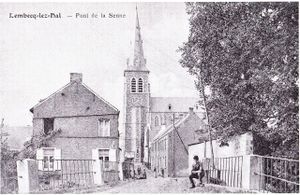

[[File:OldBridgeOverSenne.jpg|thumb|Old postcard showing a bridge going into the town of Lembecq]] | |||

The town of Lembeek is situated less than 14 miles away from the center of Brussels in Flemish Brabant. Though the town’s name bears an uncanny orthographic resemblance to the Dutch word ''lambiek'' it is still only speculation that the name for the famous beer derived from this city’s name. Once part of the larger French kingdom and situated on one of the unofficial language borders within Belgium, the original French name for the small commune of Lembeek, Lembecq, is also reminiscent of ''lambic'' and has a similar appellative pattern as other towns in northeastern France/western Belgium coming down from the Picard dialect. | The town of Lembeek is situated less than 14 miles away from the center of Brussels in Flemish Brabant. Though the town’s name bears an uncanny orthographic resemblance to the Dutch word ''lambiek'' it is still only speculation that the name for the famous beer derived from this city’s name. Once part of the larger French kingdom and situated on one of the unofficial language borders within Belgium, the original French name for the small commune of Lembeek, Lembecq, is also reminiscent of ''lambic'' and has a similar appellative pattern as other towns in northeastern France/western Belgium coming down from the Picard dialect. | ||

The suffix ''-bec[q]'', from an appellative standpoint derives from Old English and Old Norse and can either signify ‘''stream''’ or ‘''brook''’ or, with the addition of the | The suffix ''-bec[q]'', from an appellative standpoint derives from Old English and Old Norse and can either signify ‘''stream''’ or ‘''brook''’ or, with the addition of the [q], ''‘slope’'', ''‘incline’'', or ''‘hill.’'' Either is appropriately fitting for the town of Lembecq as it is situated on the Senne River as well as part of the surrounding valley. The town itself is rarely referred to today as Lembecq, as it was absorbed by the city of Hal (Dutch: Halle) over the years. The Dutch name, Lembeek, shows the similar suffix ''–beek'' meaning ''‘creek’'' or ''‘stream’'' and can be seen in a number of towns in the area (see chart above). The prefix for the town ''lem-'' can also be found in the Dutch word ''‘leemstreek’'' which is a large area of land over which loam soil (heavy in silt and sand) has been deposited. Dialect changes likely led to the shortening of ''leem–'' to ''lem–'' helping to name the town of Lembeek. | ||

Formerly home to many small pubs and breweries, especially during the industrial revolution, the town of Lembeek/Lembecq is now home to one of the most prolific lambic breweries and blenders, [[Brouwerij Boon|Brouwerij Boon]], which is situated a stone’s throw away from the Senne river. Lembeek is now part of | Formerly home to many small pubs and breweries, especially during the industrial revolution, the town of Lembeek/Lembecq is now home to one of the most prolific lambic breweries and blenders, [[Brouwerij Boon|Brouwerij Boon]], which is situated a stone’s throw away from the Senne river. Lembeek is now part of Flemish Brabant and is primarily Belgo-Dutch speaking, resulting in the majority of Boon’s lambics receiving Dutch names. Additionally, the older French spellings of this town include ''Linbecq'' and ''Lambecq'' and could have come from an older French language description of the town as the ''village d'alambic'' or ''town of alambic'' (stills).<ref name=GeuzeKriek>Jef Van den Steen, [[Books#Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer|Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer]], 2012</ref> | ||

==Lambic, Lambiek, Lambik, and Lambick== | |||

Concerning the word ''lambic'' itself, it is common to see three separate spellings that vary between locations, brewers, and even beers. The entry for ''lambic'' in the Oxford English Dictionary gives an alternate fourth English spelling as ''lambick'' initially published in the first edition of The Century Dictionary in New York between 1889-1891 and defined as “a kind of strong beer made in Belgium by the process called the self-fermentation of worts.” This conventional English spelling of the French term ''lambic'' has largely been dropped over time in favor of the French spelling among English Speakers. Past this, the etymological history of ''lambic'' is partly speculative, partly anecdotal, and partly verifiable. | |||

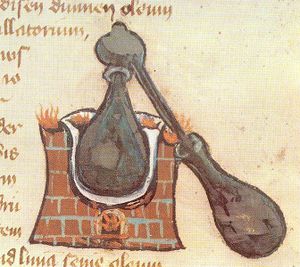

[[File:AlembicStill.jpg|thumb|left|Alembic still from a Medieval manuscript. Source: Wikipedia]] | |||

Guinard (1990) writes that “according to a writer from the Tirailleur newspaper in 1893, the term lambic has its origin in the peasants’ belief that lambic, being very harsh to the palate, was actually a distilled beverage.”<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> This is not completely out of the realm of possibility, as the traditional stills of the era were alembic-style stills, and ale has always historically been associated with the peasantry in Europe. The French spelling of alembic, ''alambic'' is still closely associated with the brandy industry today as the specific still used for cognac and Armagnac production. An alembic is actually the lid that covers the flask-apparatus of the still, but is often used to refer to the entire distilling apparatus. | |||

Guinard (1990) | Belgian historian Godefroi Kurth has also noted, according to Guinard (1990), that the term alambic was also the old name for the mashing vessel used to brew lambic beer. Mashtuns of the time can be similar in shape and construction to the alembic stills of the day.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> The word alembic itself derives from both Arabic, ''al-anbīq'', and Greek, ''ambyx'', potentially placing the birthplace of lambic vocabulary very far from its ancestral home in the Pajottenland. Given the proliferation of Latin as a language of both study and commerce throughout the post-Greek world, it is also interesting to note that the Latin infinitive verb ''lambere'' takes a conjugated meaning of t''o lick/lap up/absorb'', possibly lending itself to any number of derivative languages in various forms, including the realm of fermented beverages. | ||

As previously discussed, there is no proven etymological history with the word ''lambic''. It has also been noted that the word for the beer is just as likely to have originated from the town of Lembeek where [[Brouwerij Boon|Brouwerij Boon]] still produces lambic today. Lambic breweries outside of Brussels proper almost exclusively use Belgo-Dutch terminology. There are two commonly accepted spellings of lambic in the Belgo-Dutch dialect: lambiek and lambik. The absence of the ''/e/'' carries little phonological difference, and the spelling decision is one of personal preference only. [[De Cam Geuzestekerij|De Cam]], for example, labels an [[De_Cam_Geuzestekerij_Oude_Lambiek_De_Cam|Oude Lambiek De Cam]], while [[Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen|Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen]] has been known to use both Lambik and Lambiek on labels and in press. Thus, as the variation in ''lambic/lambiek/lambik'' and its etymological history remains up for debate, there are several historical strands that seem to help form its usage and spelling today. | |||

'' | |||

==Gueuze, Geuze== | |||

[[File:FrenchFirstRepublic.png|thumb|France under The First Republic. The departement of Dyle, containing Brussels and much of the Pajottenland, can be seen in the Northeast corner in pink. Source: Wikipedia ]] | |||

Just as with the term ''lambic'', there is still no general consensus on the etymological history of the word ''gueuze'' as it relates to beer. Gueuze is the French spelling whereas geuze is used in the Belgo-Dutch dialect. Present-day Lembecq was initially part of the French département of Dyle under The First Republic of France. Created in 1795, Dyle’s primary urban city was Brussels, solidifying its position as a French-speaking region until it was handed over to the Netherlands in 1815 after the fall of Napoleon I. In the years between 1815 and 1830, when Belgium gained its political and territorial independence from the Netherlands, the town remained a quasi French-speaking area of Flemish Brabant. | |||

Guinard (1990) claims that it was in the town of Lembecq where the gueuze appellation was born. He writes that in 1870 “the mayor of Lembecq, who owned a brewery, hired an engineer by the name of Cayaerts. Together, they decided to apply the ''méthode Champenoise'' to referment lambic beer in a bottle.” It was initially called ''“lambic des gueux”'' as a nod to the mayor’s liberal political party.<ref name="Guinard">Jean-Xavier Guinard, [[Books#Classic Beer Styles: Lambic|Classic Beer Styles: Lambic]], 1990</ref> Acknowledging again the important role that beer has played among the peasantry, it is interesting to note that the word “''gueux''” can best be translated as the obscure French word for beggar or commoner and that the feminine form of the noun is ''gueuse.'' The feminine form of the word is used today as a derogatory word for a woman but bears no phonological difference to the word ''gueuze''. Should this story hold true, as further research is needed, then the linguistic home of gueuze is very closely tied to its geographical home of the Pajottenland. | |||

Looking into the words ''gueux/gueuse'' (French) and ''geuze/geuzen'' (Dutch) the historical strand becomes clearer. While it is unclear which term came first (French of Dutch) or if they existed simultaneously, the plural Dutch word ''Geuzen'' historically identifies a group of Calvinist Dutch nobles who opposed the Spanish rule of the Netherlands between 1581 to 1714. It can also be used to refer to a subset of historical beggars, pirates, or privateers in Dutch.<ref name = GezueEnHumanisme> Hubert Van Heereweghen, [[Books#Geuze_en_Humanisme|Geuze en Humanisme]], 1955 (2010) </ref> As Spanish power waned in the early part of the 18th century, France repeatedly invaded the territory. French incursions into the area forged linguistic ties in Flemish Brabant, and the County of Hainaut (now part of present-day France and Belgium (where Hal/Halle/Lembecq) is located), and remain an integral part of lambic history today. | |||

From a phonological standpoint there is very little variation in the words ''gueuze'' (French) and ''geuze'' (Dutch). The initial French masculine noun of ''geux'' receives the [se] after dropping the [x] in the feminine form resulting in a final ''/z/'' sound, which is how the French spell it today. The Dutch spelling varies slightly dropping the initial [u] while still retaining the final ''/z/'' sound in a slightly more emphasized and elongated manner. The plural forms of the word in both French and Dutch retain normal grammatical rules respective of their languages, thus transforming the name of the beer back into either a word meaning ‘beggars’ or ‘commoners’ for French or a group of malcontents in Dutch. | |||

The use of ''gueuze'' and ''geuze'' today varies brewery by brewery just as the term lambic and lambi[e]k does. The spelling of the word generally follows the geographic-linguistic placement of the brewery using it, but it should be noted that this is not always the case. [[Brouwerij Girardin|Brouwerij Girardin]], which bears a mixed Dutch/French name and is situated in the Belgo-Dutch speaking region of St. Ulrik’s Kapelle, uses the French term ''gueuze'' for their [[Gueuze 1882 (Black label)|Gueuze Girardin]] bottlings. The same holds true for [[Brouwerij Lindemans|Brouwerij Lindemans]] who uses the mixed French-Dutch term for their [[Oude_Gueuze_Cuvée_René|Oude Gueuze Cuvée René]]. | |||

The | ==The Brussels Grand Cru== | ||

[[File:Label Cantillon Bruocsella2001.jpg|thumb|left|Grand Cru Bruocsella, 2001]] | |||

In [[Books#Gueuze.2C_Faro_et_Kriek|''Gueuze, Faro, et Kriek'']], author Raymond Buren discusses the origin of the word "Bruoc-Sela". He notes that the village of Bruoc-Sela was founded in 979 when Charles of France, Duke of Lower Lorraine established a fort on a small island in the Senne River. Indeed, the city of Brussels officially held its first millennial celebration in 1979. However, the name appears over 200 years earlier in the historical record when Saint Vindicien, Bishop of Arras and Cambai passed away in the village of Bruc-selle in 706.<ref name=GeuzeFaroEtKriek>Raymond Buren, [[Books#Gueuze.2C_Faro_et_Kriek|Gueuze, Faro, et Kriek]], 1992</ref> Sociolinguist Michel de Coster notes that the word ''bruoc'' most likely derives from the Celtic word meaning a swampy or marshy place, while the word ''sella'' comes from the Latin term meaning temple, owning to the various Roman ruins in the area at the time, chamber, or dwelling.<ref name=BrusselsLanguage>Michel de Coster, Les Enjeux du Conflit Linguistique : Le Français à l’Epreuve des Modèles Belge, Suisse et Canadien, 2007</ref> Thus the area around present-day Brussels became known as Bruoc-selle or Bruoc-sella, depending on the year or text, eventually evolving into the French Bruxelles with other alternate spellings appearing over time. This is further evidenced by two other etymological developments in old Dutch wherein the word ''broek'' at one time meant brook or marsh and ''zele'' meant settlement. In the Flemish-Dutch dialect, Broekzele still exists as a rare word to refer to the Belgian capital of Brussels. In the end, Bruocsella Grand Gru is the Brussels Grand Cru. | |||

==The Language of Fruit== | |||

Perhaps one of the more interesting aspects of the language of lambic is the language of fruit. Fruit plays an integral part of flavoring lambics, but there is an interesting admixture of languages when it comes to naming these fruit lambics. The discerning lambic drinker will realize that they have rarely, if ever, seen a bottle of “''Lambic de Cerise'',” French for cherry lambic, in production anywhere. The breweries that generally use French terminology such as [[Brasserie Cantillon|Cantillon]] still refer to their cherry lambic by the specifically Flemish (not Dutch) word ''kriek'', which refers to the sour Morello cherry. The decision to use one term over the other generally does not fall along lambic/lambiek lines, as kriek is almost universally used among lambic brewers and blenders. The single known exception to this universal cherry trend is a beer brewed by Cantillon named [[Cantillon_Kersengueuze|Kersengueuze]]. ''Kers'' (''kersen'', plural) is the Dutch word for cherry and Kersengueuze was an experimental beer that used sweet cherries instead of sour cherries for the majority of the fruit. | |||

In terms of raspberries, another popular fruit for lambics, both the terms ''framboise'' (French) and ''framboos'' (''frambozen'', plural) (Dutch) are used. The decision to use one term over the other generally does fall along lambic/lambiek lines, with some exceptions. Cantillon, for example, uses framboise, whereas De Cam also uses a French/Dutch combination for their [[De_Cam_Geuzestekerij_Framboise_Lambiek|Framboise Lambiek.]] | |||

Less common than either cherry or raspberry are subsets of grapes to flavor lambics. Generally, especially in the case of Cantillon, these beers are given specific names not having anything to do with the grapes. Historically, though, the Dutch word for grape, ''druif'' (''druiven'', plural), has been used in two instances: [[Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen|Drie Fontienen]] [[3_Fonteinen_Druiven_Geuze|Druiven Geuze]] (later renamed [[3_Fonteinen_Malvasia_Rosso|Malvasia Rosso]], named for the specific grape) and Cantillon [[Cantillon_Druivenlambik_(Cuvée_Neuf_Nations)|Druivenlambiek]] (also named ''Lambic de Raisin'' on a fully bilingual label). | |||

While many other fruits (apricots, blueberries, blackberries, grape varietals, currants, and a wide variety of rare berries) are used to fruit lambics, the names for the fruits are generally not used in their respective French and Belgo-Dutch forms. One exception to the above list is Cantillon’s [[Cantillon_Blåbær_Lambik|Blåbær Lambik]], with ''blåbær'' being Danish for blueberry (bilberry). | |||

Interestingly, one producer currently stands alone in their use of a particular fruit: the plum. [[Gueuzerie Tilquin]], in French Wallonia, uses plums in their [[Oude_Quetsche_Tilquin_à_L'Ancienne|Oude Quetsche Tilquin à l’Ancienne]]. ''Quetsche'', being the French word for a particular type of Damson plum, has its roots in the Germanic Moselle Franconia dialect as well as in Franco-Germanic dialect from Alsace. The word ''quetsche'' also has its German equivalent in the word ''Zwetschge.'' | |||

Even within the small subset of lambic brewing and blending there is a rich linguistic history that is brought to light in the terminology and usage between two distinct language groups. Though it is true that Belgium has had a long history of linguistic division, it is also evident that, at least within the lambic brewing world, there is some friendly crossover. After 1794 when the territory of Belgium was integrated into the larger French empire, the French language was fully imposed upon all of its citizens. After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna proclaimed the "Kingdom of the Netherlands" which included Belgium. The new king, a Dutchman, imposed the Dutch language on the entire kingdom. Both Walloon and Flemish people revolted against this authoritarian king and more revolts took place that eventually led to the creation of an independent Belgium in 1830. The current Belgian constitution calls for three economically autonomous regions in Belgium (Wallonia, Flanders, and Brussels), and lambic breweries are situated in all three of them. For the lambic fan, drinking in some of the language history can go a long way in helping to appreciate the rich story of the beer, its homeland, and its purveyors. | ==Conclusion== | ||

Even within the small subset of lambic brewing and blending, there is a rich linguistic history that is brought to light in the terminology and usage between two distinct language groups. Though it is true that Belgium has had a long history of linguistic division, it is also evident that, at least within the lambic brewing world, there is some friendly crossover. After 1794 when the territory of Belgium was integrated into the larger French empire, the French language was fully imposed upon all of its citizens. After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna proclaimed the "Kingdom of the Netherlands" which included Belgium. The new king, a Dutchman, imposed the Dutch language on the entire kingdom. Both Walloon and Flemish people revolted against this authoritarian king and more revolts took place that eventually led to the creation of an independent Belgium in 1830. The current Belgian constitution calls for three economically autonomous regions in Belgium (Wallonia, Flanders, and Brussels), and lambic breweries are situated in all three of them. For the lambic fan, drinking in some of the language history can go a long way in helping to appreciate the rich story of the beer, its homeland, and its purveyors. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[An_Overview_of_Lambic|← An Overview of Lambic]] | |||

Latest revision as of 04:09, 26 September 2018

The Language of Lambic: Linguistic Differentiation and Etymological History in Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French Lambic Terminology

Making sense of the terminology surrounding lambic can be as complex as the beer itself. Belgium is a country divided into very distinct linguistic regions whose inhabitants have their own words for many of the commonly used terms associated with the lambic tradition and process. Both Dutch and French speaking brewers and blenders are in operation today leaving many curious lambic drinkers wondering how this all came to be. In addition to the following article, readers may also find the Lambic.Info Glossary a helpful resource as they browse this site.

Introduction

The language diversity contained within the modern-day borders of Belgium provides a source of constant linguistic conflict in the Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French speaking populations that dominates 94% of the population (56% and 38% respectively as a first language). Looking at a linguistic map of Belgium one notices that the capital of Brussels is squarely planted in an area dominated by the Belgo-Dutch dialect (sometimes referred to as Flemish in English). The capital area is officially regarded as bilingual by the Belgian government, but a survey of languages overheard walking around town leans toward the Bruxellois dialect of French. The dichotomy between these Belgo-Dutch speakers and Belgo-French speakers plays out on a number of social and political levels throughout the country, and within the lambic brewing and blending community one can still see and hear the differences today. The purpose of this article is to explore the historical, etymological, linguistic, and orthographic differences found among lambic terminology, labeling, and appellation. This article freely switches between Belgo-Dutch and Belgo-French where appropriate, though the orthographic difference is often minimal.

Overview of Linguistic and Administrative Divisions in Belgium

To fully understand how the language of lambic came to be used among the brewers, it is first necessary to have a general overview of how the country of Belgium is administered. Belgium is divided into three regions, three communities, and four language areas. The three regions compose of the Flemish region (Dutch speaking), the Brussels-Capital region (officially bilingual), and the Walloon region (French speaking). Within the Flemish and Walloon regions there are five provinces each. The Belgian-Capital region does not have any official provincial designation nation and acts as its own community. The fourth language area is a small minority of German speaking Belgians in the east of the country.

The provincial divisions in the Flemish Region are West Flanders, East Flanders, Antwerp, Flemish Brabant, and Limburg. The provincial divisions in the Walloon region are Hainaut, Walloon Brabant, Namure, Liège, and Luxembourg. It is important to note that most lambic breweries and blenders fall into either the Flemish region or the Brussels-Capital regions. From here, the brewery's languages can now be better understood.

Brewery Locations

Most present-day lambic breweries and blenders, as well as those that are no longer in operation, are situated in and around the Zenne valley in the Pajottenland area of Belgium. This area, consisting of mostly farmland, is part of the Flemish Brabant province and sits just west of the Brussels capital area. Though Brussels is primarily Belgo-French speaking, the area that surrounds the city to the north, east, and west is predominantly Belgo-Dutch speaking. This has led to very few breweries actually using the French terminology in lambic brewing on a consistent basis over the years. Currently, the only truly traditional lambic brewery located in Brussels using primarily French terminology for labeling, press, and first language tours is Brasserie Cantillon.

The only traditional lambic blender outside of Brussels currently using French terminology is Gueuzerie Tilquin. Located in the town of Bierghes, in the Senne valley, it is the only gueuze blender in the primarily French-speaking Walloon Brabant region situated within the administrative commune of Rebecq. Two less-than-traditional lambic breweries, Brasserie Mort Subite and Brasserie Belle-Vue, currently use French terminology, however; only Brasserie Belle-Vue is located in Brussels. It is currently owned by the international conglomerate of Anheuser-Busch InBev whose European headquarters are located in the Dutch-speaking city of Leuven east of Brussels. The rest of the prominent lambic brewers and blenders are mostly situated west/southwest of Brussels and primarily use the Belgo-Dutch dialect.

The names of cities that breweries use in their official addresses give a good idea of the general linguistic approach taken by the company. Many towns in Belgium, regardless of their regional location have both a French and a Dutch name. Some brewers have historically used both names in labeling, while others have stuck to one. The following table shows a list of currently operating brewers and blenders, their locations in both Dutch and French (if available), and their preferred use.

| Brewer | Province | Town/Village (Dutch) | Town/Village (French) | Currently using: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Fonteinen | Vlaams-Brabant | Beersel | N/A | Dutch |

| Belle-Vue | Vlaams-Brabant | Sint-Pieters-Leeuw | Leeuw-Saint-Pierre | French |

| Boon | Vlaams-Brabant | Lembeek | Lembecq | Dutch |

| Cantillon | Région de Bruxelles-Capitale | Brussel | Bruxelles | French |

| De Cam | Vlaams-Brabant | Gooik | N/A | Dutch |

| De Troch | Vlaams-Brabant | Wambeek | N/A | Dutch, some French |

| Girardin | Vlaams-Brabant | Sint-Ulriks-Kapelle | Chapelle-Saint-Ulric | Dutch, some French |

| Hanssens | Vlaams-Brabant | Dworp | Tourneppe | Dutch |

| Lindemans | Vlaams-Brabant | Vlezenbeek | N/A | Dutch, some French |

| Mort Subite | Vlaams-Brabant | Kobbegem | Kobbeghem | Dutch, some French |

| Oud Beersel | Vlaams-Brabant | Beersel | N/A | Dutch |

| Timmermans | Vlaams-Brabant | Itterbeek | N/A | Dutch, some French |

| Tilquin | Province du Brabant wallon | Roosbeek | Rebecq-Rognon | French |

The Town of Lembeek

The town of Lembeek is situated less than 14 miles away from the center of Brussels in Flemish Brabant. Though the town’s name bears an uncanny orthographic resemblance to the Dutch word lambiek it is still only speculation that the name for the famous beer derived from this city’s name. Once part of the larger French kingdom and situated on one of the unofficial language borders within Belgium, the original French name for the small commune of Lembeek, Lembecq, is also reminiscent of lambic and has a similar appellative pattern as other towns in northeastern France/western Belgium coming down from the Picard dialect. The suffix -bec[q], from an appellative standpoint derives from Old English and Old Norse and can either signify ‘stream’ or ‘brook’ or, with the addition of the [q], ‘slope’, ‘incline’, or ‘hill.’ Either is appropriately fitting for the town of Lembecq as it is situated on the Senne River as well as part of the surrounding valley. The town itself is rarely referred to today as Lembecq, as it was absorbed by the city of Hal (Dutch: Halle) over the years. The Dutch name, Lembeek, shows the similar suffix –beek meaning ‘creek’ or ‘stream’ and can be seen in a number of towns in the area (see chart above). The prefix for the town lem- can also be found in the Dutch word ‘leemstreek’ which is a large area of land over which loam soil (heavy in silt and sand) has been deposited. Dialect changes likely led to the shortening of leem– to lem– helping to name the town of Lembeek.

Formerly home to many small pubs and breweries, especially during the industrial revolution, the town of Lembeek/Lembecq is now home to one of the most prolific lambic breweries and blenders, Brouwerij Boon, which is situated a stone’s throw away from the Senne river. Lembeek is now part of Flemish Brabant and is primarily Belgo-Dutch speaking, resulting in the majority of Boon’s lambics receiving Dutch names. Additionally, the older French spellings of this town include Linbecq and Lambecq and could have come from an older French language description of the town as the village d'alambic or town of alambic (stills).[1]

Lambic, Lambiek, Lambik, and Lambick

Concerning the word lambic itself, it is common to see three separate spellings that vary between locations, brewers, and even beers. The entry for lambic in the Oxford English Dictionary gives an alternate fourth English spelling as lambick initially published in the first edition of The Century Dictionary in New York between 1889-1891 and defined as “a kind of strong beer made in Belgium by the process called the self-fermentation of worts.” This conventional English spelling of the French term lambic has largely been dropped over time in favor of the French spelling among English Speakers. Past this, the etymological history of lambic is partly speculative, partly anecdotal, and partly verifiable.

Guinard (1990) writes that “according to a writer from the Tirailleur newspaper in 1893, the term lambic has its origin in the peasants’ belief that lambic, being very harsh to the palate, was actually a distilled beverage.”[2] This is not completely out of the realm of possibility, as the traditional stills of the era were alembic-style stills, and ale has always historically been associated with the peasantry in Europe. The French spelling of alembic, alambic is still closely associated with the brandy industry today as the specific still used for cognac and Armagnac production. An alembic is actually the lid that covers the flask-apparatus of the still, but is often used to refer to the entire distilling apparatus.

Belgian historian Godefroi Kurth has also noted, according to Guinard (1990), that the term alambic was also the old name for the mashing vessel used to brew lambic beer. Mashtuns of the time can be similar in shape and construction to the alembic stills of the day.[2] The word alembic itself derives from both Arabic, al-anbīq, and Greek, ambyx, potentially placing the birthplace of lambic vocabulary very far from its ancestral home in the Pajottenland. Given the proliferation of Latin as a language of both study and commerce throughout the post-Greek world, it is also interesting to note that the Latin infinitive verb lambere takes a conjugated meaning of to lick/lap up/absorb, possibly lending itself to any number of derivative languages in various forms, including the realm of fermented beverages.

As previously discussed, there is no proven etymological history with the word lambic. It has also been noted that the word for the beer is just as likely to have originated from the town of Lembeek where Brouwerij Boon still produces lambic today. Lambic breweries outside of Brussels proper almost exclusively use Belgo-Dutch terminology. There are two commonly accepted spellings of lambic in the Belgo-Dutch dialect: lambiek and lambik. The absence of the /e/ carries little phonological difference, and the spelling decision is one of personal preference only. De Cam, for example, labels an Oude Lambiek De Cam, while Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen has been known to use both Lambik and Lambiek on labels and in press. Thus, as the variation in lambic/lambiek/lambik and its etymological history remains up for debate, there are several historical strands that seem to help form its usage and spelling today.

Gueuze, Geuze

Just as with the term lambic, there is still no general consensus on the etymological history of the word gueuze as it relates to beer. Gueuze is the French spelling whereas geuze is used in the Belgo-Dutch dialect. Present-day Lembecq was initially part of the French département of Dyle under The First Republic of France. Created in 1795, Dyle’s primary urban city was Brussels, solidifying its position as a French-speaking region until it was handed over to the Netherlands in 1815 after the fall of Napoleon I. In the years between 1815 and 1830, when Belgium gained its political and territorial independence from the Netherlands, the town remained a quasi French-speaking area of Flemish Brabant.

Guinard (1990) claims that it was in the town of Lembecq where the gueuze appellation was born. He writes that in 1870 “the mayor of Lembecq, who owned a brewery, hired an engineer by the name of Cayaerts. Together, they decided to apply the méthode Champenoise to referment lambic beer in a bottle.” It was initially called “lambic des gueux” as a nod to the mayor’s liberal political party.[2] Acknowledging again the important role that beer has played among the peasantry, it is interesting to note that the word “gueux” can best be translated as the obscure French word for beggar or commoner and that the feminine form of the noun is gueuse. The feminine form of the word is used today as a derogatory word for a woman but bears no phonological difference to the word gueuze. Should this story hold true, as further research is needed, then the linguistic home of gueuze is very closely tied to its geographical home of the Pajottenland.

Looking into the words gueux/gueuse (French) and geuze/geuzen (Dutch) the historical strand becomes clearer. While it is unclear which term came first (French of Dutch) or if they existed simultaneously, the plural Dutch word Geuzen historically identifies a group of Calvinist Dutch nobles who opposed the Spanish rule of the Netherlands between 1581 to 1714. It can also be used to refer to a subset of historical beggars, pirates, or privateers in Dutch.[3] As Spanish power waned in the early part of the 18th century, France repeatedly invaded the territory. French incursions into the area forged linguistic ties in Flemish Brabant, and the County of Hainaut (now part of present-day France and Belgium (where Hal/Halle/Lembecq) is located), and remain an integral part of lambic history today.

From a phonological standpoint there is very little variation in the words gueuze (French) and geuze (Dutch). The initial French masculine noun of geux receives the [se] after dropping the [x] in the feminine form resulting in a final /z/ sound, which is how the French spell it today. The Dutch spelling varies slightly dropping the initial [u] while still retaining the final /z/ sound in a slightly more emphasized and elongated manner. The plural forms of the word in both French and Dutch retain normal grammatical rules respective of their languages, thus transforming the name of the beer back into either a word meaning ‘beggars’ or ‘commoners’ for French or a group of malcontents in Dutch.

The use of gueuze and geuze today varies brewery by brewery just as the term lambic and lambi[e]k does. The spelling of the word generally follows the geographic-linguistic placement of the brewery using it, but it should be noted that this is not always the case. Brouwerij Girardin, which bears a mixed Dutch/French name and is situated in the Belgo-Dutch speaking region of St. Ulrik’s Kapelle, uses the French term gueuze for their Gueuze Girardin bottlings. The same holds true for Brouwerij Lindemans who uses the mixed French-Dutch term for their Oude Gueuze Cuvée René.

The Brussels Grand Cru

In Gueuze, Faro, et Kriek, author Raymond Buren discusses the origin of the word "Bruoc-Sela". He notes that the village of Bruoc-Sela was founded in 979 when Charles of France, Duke of Lower Lorraine established a fort on a small island in the Senne River. Indeed, the city of Brussels officially held its first millennial celebration in 1979. However, the name appears over 200 years earlier in the historical record when Saint Vindicien, Bishop of Arras and Cambai passed away in the village of Bruc-selle in 706.[4] Sociolinguist Michel de Coster notes that the word bruoc most likely derives from the Celtic word meaning a swampy or marshy place, while the word sella comes from the Latin term meaning temple, owning to the various Roman ruins in the area at the time, chamber, or dwelling.[5] Thus the area around present-day Brussels became known as Bruoc-selle or Bruoc-sella, depending on the year or text, eventually evolving into the French Bruxelles with other alternate spellings appearing over time. This is further evidenced by two other etymological developments in old Dutch wherein the word broek at one time meant brook or marsh and zele meant settlement. In the Flemish-Dutch dialect, Broekzele still exists as a rare word to refer to the Belgian capital of Brussels. In the end, Bruocsella Grand Gru is the Brussels Grand Cru.

The Language of Fruit

Perhaps one of the more interesting aspects of the language of lambic is the language of fruit. Fruit plays an integral part of flavoring lambics, but there is an interesting admixture of languages when it comes to naming these fruit lambics. The discerning lambic drinker will realize that they have rarely, if ever, seen a bottle of “Lambic de Cerise,” French for cherry lambic, in production anywhere. The breweries that generally use French terminology such as Cantillon still refer to their cherry lambic by the specifically Flemish (not Dutch) word kriek, which refers to the sour Morello cherry. The decision to use one term over the other generally does not fall along lambic/lambiek lines, as kriek is almost universally used among lambic brewers and blenders. The single known exception to this universal cherry trend is a beer brewed by Cantillon named Kersengueuze. Kers (kersen, plural) is the Dutch word for cherry and Kersengueuze was an experimental beer that used sweet cherries instead of sour cherries for the majority of the fruit.

In terms of raspberries, another popular fruit for lambics, both the terms framboise (French) and framboos (frambozen, plural) (Dutch) are used. The decision to use one term over the other generally does fall along lambic/lambiek lines, with some exceptions. Cantillon, for example, uses framboise, whereas De Cam also uses a French/Dutch combination for their Framboise Lambiek.

Less common than either cherry or raspberry are subsets of grapes to flavor lambics. Generally, especially in the case of Cantillon, these beers are given specific names not having anything to do with the grapes. Historically, though, the Dutch word for grape, druif (druiven, plural), has been used in two instances: Drie Fontienen Druiven Geuze (later renamed Malvasia Rosso, named for the specific grape) and Cantillon Druivenlambiek (also named Lambic de Raisin on a fully bilingual label).

While many other fruits (apricots, blueberries, blackberries, grape varietals, currants, and a wide variety of rare berries) are used to fruit lambics, the names for the fruits are generally not used in their respective French and Belgo-Dutch forms. One exception to the above list is Cantillon’s Blåbær Lambik, with blåbær being Danish for blueberry (bilberry).

Interestingly, one producer currently stands alone in their use of a particular fruit: the plum. Gueuzerie Tilquin, in French Wallonia, uses plums in their Oude Quetsche Tilquin à l’Ancienne. Quetsche, being the French word for a particular type of Damson plum, has its roots in the Germanic Moselle Franconia dialect as well as in Franco-Germanic dialect from Alsace. The word quetsche also has its German equivalent in the word Zwetschge.

Conclusion

Even within the small subset of lambic brewing and blending, there is a rich linguistic history that is brought to light in the terminology and usage between two distinct language groups. Though it is true that Belgium has had a long history of linguistic division, it is also evident that, at least within the lambic brewing world, there is some friendly crossover. After 1794 when the territory of Belgium was integrated into the larger French empire, the French language was fully imposed upon all of its citizens. After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna proclaimed the "Kingdom of the Netherlands" which included Belgium. The new king, a Dutchman, imposed the Dutch language on the entire kingdom. Both Walloon and Flemish people revolted against this authoritarian king and more revolts took place that eventually led to the creation of an independent Belgium in 1830. The current Belgian constitution calls for three economically autonomous regions in Belgium (Wallonia, Flanders, and Brussels), and lambic breweries are situated in all three of them. For the lambic fan, drinking in some of the language history can go a long way in helping to appreciate the rich story of the beer, its homeland, and its purveyors.

References

- ↑ Jef Van den Steen, Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic Beer, 2012

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jean-Xavier Guinard, Classic Beer Styles: Lambic, 1990

- ↑ Hubert Van Heereweghen, Geuze en Humanisme, 1955 (2010)

- ↑ Raymond Buren, Gueuze, Faro, et Kriek, 1992

- ↑ Michel de Coster, Les Enjeux du Conflit Linguistique : Le Français à l’Epreuve des Modèles Belge, Suisse et Canadien, 2007