Lambic.Info Logo

Below the Lambic.Info logo a saying in French reads « Après avoir terrassé le dragon, l’ange boit à votre santé. » Loosely translated to English it means “After slaying the dragon, the angel toasts to your health.” The saying and original illustration come from the very last page of an important work of early lambic literature titled "Les Memoirs de Jef Lambic” written and illustrated by Robert Desart, a Belgian folkloric artist. No other explanation was given except for the phrase and the original image, and it immediately jumped out at us. We decided to dig deeper into the origin of the image and the meaning behind the phrase and adapt it for our logo here. What is still unknown is the inspiration for the original sign drawing by Robert Desart in the back of Les Memoris de Jef Lambic and where the saying came from. It may be nothing more than a picture imagined by Desart in 1955 as he was illustrating the book, but it may also be a depiction of a real sign, possibly even still hanging above a door to an estaminet or café in an undiscovered corner of Brussels. Our hope is to someday find the original and uncover more of its history. The idea to adapt this logo for the project comes both out of respect for the cultural history of lambic and from the continued research that it represents.

New Findings, 2018

Throughout 2017 and 2018, Gaëtan Claes of 3 Fonteinen provided a thoroughly researched and referenced background on the origins of the Lambic.Info logo as well as its potential author. We are extremely grateful for the vast amount of new information that has come to light through Gaëtan's work!

An Alternative to Saint George

At first sight when looking at the lambic.info logo, one cannot but link it to the story of St. Georges. Living in a “Christian” country like Belgium it immediately points in the direction of this dragonslaying saint, as the story is well-known and there is an obvious beer-connection. Traditionally the brewing season for “regular” beer was very similar to the lambic brewing season nowadays. To protect the beer from infection e.a. one could only brew during cold weather. As a matter of fact the official end date was the 23rd of April, the date of death of … St. Georges. Brewing was prohibited from that day until the 29th of September, the Christian Feast of St. Michael, archangel Michael that is. In order to bridge the gap here it is necessary to point out that archangel Michael too overpowered a dragon, and a very important one too. As St. Georges killed a dragon only for his own benefit, or Christianity’s, St. Michael overpowered a dragon for the benefit of us, mankind. Let me tell you the story of Michael.

The story of archangel Michael can be found in the last part of the New Testament and thus the

Bible, the Book of Revelation (attributed to John the Apostle). It describes the Apocalyptic battle, the War in Heaven (Revelation 12:7-9):

7 Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. 8 But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. 9 The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray. He was hurled to the earth, and his angels with him.

Although “the dragon” obviously stands for the devil and evil in general, depictions of this scene rather do show the archangel overpowering a dragon, and not the devil.

St. / Archangel Michael and Brussels

Ever since the 8th century St. Michael is being worshipped in the Brussels area: a place of worship could be found on a hill next to the Zenne river, alongside the Cologne-Bavaria road. When the town of Brussels emerged in the 10th century, St. Michael almost evidently became the patron saint of Brussels. The cathedral of St. Michael and St Gudula traces back to the 11th century and ever since the cult of St. Michael has been cultivated and to date a lot of references to St. Michael (mostly with dragon) can still be found. During the second half of the 19th century the city even financed the depiction of St. Michael on buildings. Nowadays, for example the official flag and logo of the city of Brussels carry his image and the archangel still looks upon its inhabitants in the Central Station and a 5m-tall golden statue of St. Michael overpowering the dragon crowns the town hall on the Grand Place.[1]

St. / Archangel Michael and (lambic) beer

Not only the Brussels cultural heritage bulges of references to St. Michael but he was also a popular symbol in commerce and advertising. Belgian beer culture in the 19th and 20th century has been studied a lot and we know “the good life” and beer was omnipresent in the capital. Of course the noble deeds of St. Michael were also commercially exploited: the sources reveal the use of the angel’s name and image for bars etc., although we must probably not overestimate the amount (cf. infra).

The most famous example by far is brewery St.-Michel (owned by the Vandenheuvel family) originally located at Rue de la Senne 9, 19,21 in the city centre, since 1806 (there also might have been another brewery St.-Michel on number 7 in the same street). Starting 1870 the use of a second building is documented, which became the new location towards the end of the century, along the Chaussee de Ninove. This does not surprise as most breweries moved out of the city centre to the Brussels periphery.

Originally brewery St.-Michel did produce lambic and faro. Unfortunately over time the Vandenheuvels chose a different direction and started to focus on more popular beers like stout, Bavarian, Pilsner and Export. The brewery became renown for the Ekla Pilsner. The name St.-Michel was changed to Vandenheuvel and the logo that initially depicted St.- Michael slowly disappeared. The brewery ceased lambic production after World War I. [2]

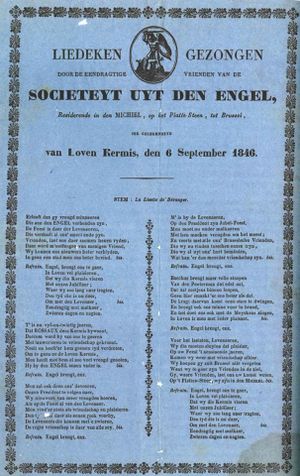

In 1846 a song text was published by the Societeyt uyt den Engel, a fraternity that resided in the bar “Den Michiel” in Brussels. Their logo shows St. Michael slaying the dragon. Nowadays few beer-references remain. But if you walk into Aux Armes de Bruxelles or café Cirio, one can still find St. Michael guarding the clients.

St. / Archangel Michael and the Lambic.Info Logo

The Lambic.Info logo has been explained as being St. Georges having slayed the dragon. The only clues to the direct meaning of this scene are the mentioning of 1) an unfortunate dragon and 2) an angel. As already pointed out, both St. Georges and St. Michael defeated a dragon but only one of them was an (arch)angel (above being a Saint), St. Michael. As we all know, Georges was “just” a Saint.

In addition to that St. Georges is almost always depicted riding a horse while stabbing the dragon, which is clearly not visible on the logo. Moreover it's important to emphasize that the text says “terrasser” which means “to overpower”, not “to kill”, though in English the most common construction is "to slay" if speaking about a dragon. When looking at the biblical texts of both St. Georges and St. Michael the first one “killed” the dragon and the latter “overpowered” it. One last element that may point to St. Michael is the fact that the author of Les mémoires de Jef Lambic was not only telling the life story of Jef Lambic (if he ever existed, cf. infra) but wanted, in my opinion, to educate the reader on folkloric and everyday life in bygone Brussels during the previous decades and mainly the turn of the 20th century. The author must have been a Brusseleir or at least someone very close to Brussels (physically or by heart). St. Michael is just around the corner…

Les mémoires de Jef Lambic: The Setup

As we all know Les mémoires de Jef Lambic is in the first place a tongue-in-cheek written folkloric account of Brussels full of (lambic)beer, humour, zwanze and again beer. But looking into detail to the text one must conclude that the author had an in depth knowledge of Brussels and insight into all day life in the previous decades. A lot of elaborated details make it a succulent story: the streets, alleys, bar scenes, facts and figures,… the book describes and even explains a real life Brussels of those days. For instance the information on lambic and the drawn evolution of the beer market is a very familiar story as a lot of foreign beers (Danish, English, German,…) did suppress lambic, faro and mars over time.

Here we must highlight the most serious part of the book, the preface. It is written by brewer Léon Wielemans, member of honour of the at the beginning of the 50s newly founded “Chevalerie du Fourquet” (let’s say a brewers guild/fraternity). He starts of his text by emphasizing the goal of the Chevalerie, i.e. keeping the tradition and history of the art of brewing in honour and at the end of the preface he regrets the fact that the old days as described in the book are gone. Not only the old beers (lambics) but also the way society ‘ticks’ these days. New technologies have taken over people’s lifes and folly, gambrinal Brussels disappeared.

Here we must consider the hypothesis that the Chevalerie asked the author to write this book (out of strong belief or/and as a promotion of the Chevalerie?) to educate people or to make sure these beers (and info) wouldn’t be forgotten over time. Is it a coincidence that two other famous odes on geuze were written during these years, Gueuze-Champagne by Albert Vossen (1954) and Geuze en Humanisme by Hubert Van Herreweghen (1955)?

Les mémoires de Jef Lambic: The Author

The author thus must have been thoroughly acquainted with all aspects of Brussels. If you take a look at the writings concerning these topics (folkloric, Brussels, beer, zwanze,…) of that time, three distinguished men could have done the job: Jean d’Osta, Louis Quiévreux and Robert Desart. Besides these three men it is important to also mention Albert Vossen of course, who was acquainted with them. We do know the lecture he gave on geuze[3] but I don’t believe the geuze-pope wrote Jef Lambic. He just wasn’t an author like the other three. But being a “Brusseleir cent pour cent” with a lot of knowledge on geuze, folklore and humour he surely must have been an invaluable source.

1) Jean d’Osta: the most renowned of these men. He was an intellectual jack of all trades. He created the figure of Jef Kazak (does it ring a bell?) and wrote a bunch of stories that are similar to Jef Lambic (just take a look at his bibliography. Louis Quiévreux was a close friend and likely knew Robert Desart.

2) Louis Quiévreux: Brussels linguist, intimate of Jean d’Osta and very close with Robert Desart. Quiévreux and Desart had a long standing relationship according to an email conversation with his daughter Anne Quiévreux. Quiévreux and Desart published many books together, Quiévreux being the writer and Desart the illustrator. Take a look at ‘Les Impasses et Vieilles Rues de Bruxelles’ for example.

But Robert Desart actually was not only the illustrator but also the author of Les Mémoires de Jef Lambic. I wanted however to introduce d’Osta and Quiévreux because their style, status, topics,… are so close to Desart that I am convinced they must have influenced Desart regarding the content.

3) Robert Desart: there are many reasons why I point in his direction.

- In 2009 the late Guy Moerenhout claimed he had a letter of Robert Desart writing to the newspaper Le Peuple on the 28th of April 1958 that he is the author of Les Mémoires de Jef Lambic. Knowing Guy Moerenhout and the priceless effort he put in his blog ‘C’était au temps où Bruxelles brassait’ and describing the old beer days in Brussels, this must be correct. Until now, I wasn’t able to verify this with a relative, but for me there is no doubt.[4]

- The other books by Robert Desart are very much in line with Jef Lambic. Stylish, but also the content. Brussels back in the days…

- At the end of Les impasses et vieilles rues de Bruxelles (published in 1969, text by Louis Quiévreux) a list (see photo) of other publications by the same author is given, which starts of with Les mémoires de Jef Lambic. Whenever a publication was a collaboration, this is clearly stipulated and in doing so, not the case for Les mémoires de Jef Lambic. Desart is being mentioned as ‘editor’ of this book (with his home address) plus he signed the book as well. The copy I consulted carries the stamped number 11, by the way.

- In 1992 an article on Robert Desart was written for the revue of Le Cercle d’Histoire de Bruxelles by Gustave Abeels (see picture). It mentions Desart as the sole author of Les Mémoires de Jef Lambic. Again the year 1958 pops up. Added to the abovementioned letter of Guy Moerenhout, I believe it is safe to say we have a definite publication date.

- On the back of the book you can find the logo of Robert Desart and his oeuvres folkloriques, a logo that returns on all his books in this series. By the way, this logo also shows St. Michel (with wings) stabbing the dragon/devil.

- Robert Desart must have clearly been familiar with lambic and it’s culture considering the topics he wrote about. He also illustrated the interview with Albert Vossen of Brasserie Vossen and the famous bar A la Mort Subite. The text of that ‘interview’ is written by Louis Quiévreux (dixit Anne Quiévreux). Desart and Quiévreux weren’t lambic-zuipers, but they did enjoy a glass of lambic now and then (dixit Anne Quiévreux).

Did Jef Lambic Exist?

By stating all the above I dismiss the possibility that there ever was a Jef Lambic who wrote his memoires (birth date 1st of April), but perhaps there was a Jef Lambic-type of person on whom the stories are generally based (one can compare it to De Witte van Zichem, a famous early 20th century book by Ernest Claes; the character actually lived in Zichem, but only few real details of his life were used for the book, the rest was invented by Ernest Claes).

It has been stated that Jef Lambic’s father worked at the De Keersmaeker brewery (later Mort Subite) in Kobbegem, but I can’t find a clue in the book, on the contrary. His father worked as a brewer in Brussels (not Kobbegem) between 1830 and 1885, whereas the De Keersmaekers only bought the brewery in Kobbegem in 1869. Jef Lambic lived in Rue des Capucins, one might suggest there could have been a brewery in that area but no other clues are given.

In 1910 Theophilé Vossen (father of the abovementioned Albert Vossen) started a blendery in Rue des Capucins 20-28. He soon adopted the name Mort Subite for his beers named after the famous game we all know the story of; he did own the bar a la Mort Subite too. Perhaps confusion arose based on a map showing the end of the 19th century situation in that quarter. It mentions the Mort Subite brewery (by the Vossen family). But this map was (re)published in 1985, and the publishers added the name and pointed out it wasn’t on the original map.[5]

Did the Lambic.Info Logo Exist In Real Life?

Perhaps it did. The style does differ from most of the other drawings in the book (pen and ink drawings according to the author list at the back of Les impasses et vieilles rues de Bruxelles; Anne Quiévreux told me Robert Desart also used the linocut-technique). It is plausible to say that is has been a bar sign and that the name of the bar was St. Michael-related.

Surprisingly there is more literature on old bar names and signs than one might think. A late 19th century document in the Brussels Archive sums up all 565 Brussels bar names, of which at least 53 have a religious connotation, but only 2 had the name “St. Michel” (one in the Hoogstraat and Kappelemarkt area and the other in the Marollen area) and 8 “the angel”.

In a 1924 article (Eigenaardige uithangborden in ‘t Brusselsche) in Eigen Schoon en De Brabander Peremans regrets the fact that a lot of brilliant Flemish bar signs (sometimes with witty texts underneath) disappeared and “French” took over. More research on this can be done. The Footnotes of the article “De Brusselse herbergen in de tweede helft van de 18e eeuw” in Eigen Schoon en de Brabander (LXII, April-May-June 1979) might lead to a decisive publication as they focus on old bars, bar signs and names. Further screening of the publications of Robert Desart, Louis Quiévreux and Jean d’Osta could be interesting as well.

However, it is more likely that the logo was never a sign nor hung up anywhere. I screened Desart’s Les vieux estaminets and Les impasses et vieilles rues de Bruxelles, the two most likely publications to bear a clue. Combined, these publications give a good (written and drawn) insight into Desarts knowledge on old streets and bars and no info is given on the actual existence of the bar sign. If it had been a “thing” one might expect a second reference. Furthermore it has all the characteristics of a “vignette”, a small drawing one puts at the beginning or end of a chapter or publication. Les vieux estaminets (1960, 750 copies published) bears a special vignette too (of the printing house of this publication, Saey) and upon finishing Les impasses et vieilles rues de Bruxelles one sees Desart’s own logo (yes, the one with St. Michael in it).

So my educated guess is that Robert Desart by drawing the lambic.info logo perhaps wanted to express a feeling, “I have overcome a difficult task” (writing the book)?

End Conclusions

- Robert Desart is the sole author of Les Mémoires (probably influenced by his friends and perhaps commissioned by the Chevalerie).

- These aren’t the real memoires of a person called Jef Lambic.

- It was published in 1958.

- There is no clear connection with Brewery Mort Subite (as we know it today).

- The Lambic.Info logo depicts St. Michael and not St. Georges.

- The Lambic.Info logo isn’t a depiction of a real bar sign, but a vignette.

Initial Research

The following research was conducted between 2013 and 2015 during the early preparations for launching this website. It has since been updated and incorporated above.

The Legend of Saint George

What do angels, dragons, and beer have in common and how did that phrase come to be on the last page of a book about Brussels lambic culture in the late 19th century? To find that answer we must go back to the episode of Saint George and the Dragon. This legend, brought back by Crusaders returning from battle, is a traditional romantic heroic tale dating to as early as the 10th century AD, though possibly earlier. Several other similar versions of this story exist from all across Europe, and it was appropriated by various cultures and groups.

The legend tells of a fictional town whose lake was home to a dragon that would spread a plague among the villagers unless he was appeased. In order to appease this dragon the townspeople fed it two sheep a day in hope that the dragon would leave them alone. When this did not work, they resorted to feeding the dragon children whose names were drawn by lottery. When the king’s daughter’s name was drawn he offered all of the gold and silver in the kingdom for her life to be spared, yet the townspeople refused. The princess, dressed as a bride, arrived at the lake ready to be fed to the dragon.

At the same time, Saint George was riding past the lake and noticed the princess and refused to leave her side. As the dragon came to eat her, George made the sign of the cross, charged the dragon on his horse, and speared him with his lance. He then returned to the town with the princess and the dragon following behind her on a leash. Shocking the townspeople with the dragon, he implored them to all convert to Christianity and be baptized. If they did this, he would slay the dragon once and for all. The townspeople agreed, the dragon was killed, and a new church was erected on the spot were the dragon was slew in honor of the Virgin Mary and Saint George.[6]

Acta Sanctorum and Jean Bolland

Though the hagiography of Saint George had been well established for centuries and his legends firmly entrenched in European and other cultures, the end of the Renaissance period in Europe saw a renewed interest in the serious study of Christian Saints and their acts and an effort to expel many of the medieval myths surrounding them. This included a detailed analysis of the acts of Saint George by Jean Bolland.[7] Bolland was among a group of Jesuit scholars who worked on and published the Acta Sanctorum (Acts of Saints) in a series of volumes between 1643 and 1794. Bolland was born in 1596 in the village of Julémont, near the city of Liège in Belgium who identified as Flemish and undoubtedly had experience with the beers made famous in Brueghel’s paintings

Saint George, The Dragon, and Beer

Though the Bollandists sought to dispel many of the legends and rumors that surrounded the various saints of Europe, the legend of Saint George had become part of the cultural and religious lore of Belgium in general, just as it had across many parts of Europe. UNESCO recognizes celebrations dating back to the 14th century in the Belgian city of Mons in Saint George’s name as an event of Intangible Cultural Heritage and Humanity. [6] With these celebrations also came the traditional feasts and drinking. As we have discussed the cultural history of lambic elsewhere, it is safe to say that as the legend of Saint George became part of the traditional story telling culture of Belgium at the time, so too did the notion of the Saint slaying the dragon and returning to drink to his success and to the prosperity of the town and its people. In Belgian terms, this means that over time the traditional drink would have been lambic. The theme of the hero returning to celebrate the slaying of a monster is not uncommon in early literature and persisted in many of the folkloric tales of early modern Europe.

Saint George is the patron saint of many places and of many things, and he is often found in reference to beer and brewing. Many breweries are either named for him or have beers alluding to him and his feats. According to Frank Boon of Brouwerij Boon, Saint George is even the patron saint of lambic brewers[8], though other sources note that it is actually Saint Veronus who is the patron saint of lambic brewers and also the town of Lembeek. This statement does have some factual backing. The Saint Veronus Church in the town does have dragon motifs, and these are atypical for the period and region in general. Many have also seen references to Cantillon’s Bière du Dragon. Though little is known about the actual beer, logos on coasters and breweriana show a pronounced dragon. At one point, there was also a “Brasserie du Dragon” whose address was the same as Cantillon’s today (56 rue Gheude B-1070 Brussels) and who listed Gueuze-Lambic and Krieken as their products. Research is still ongoing as to the origins of that name and brewery.

References

- ↑ Merchiers, Karen – Nieuw boekje en rondleiding over patroonheilige Brussel

- ↑ Moerenhout, Guy – Brasserie Vandenheuvel de Molenbeek: L'histoire

- ↑ Vossen, Albert – Champagne - Gueuze

- ↑ Morenhout, Guy – [1]

- ↑ Bierbel Forums – Jef Lambic

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 UNESCO – Processional giants and dragons in Belgium and France

- ↑ Christopher Walter - The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition, 2003

- ↑ Lambic Digest, May 12, 1994 – Mariage Parfait and the Procession of St. Veronus